Written by Shirley Johnson

Written by Shirley JohnsonAmplifying the scope, reach and validity of micro-credentials in our education, training and employment sectors could make a significant impact in lifting labour market equity, skill utilisation and productivity.

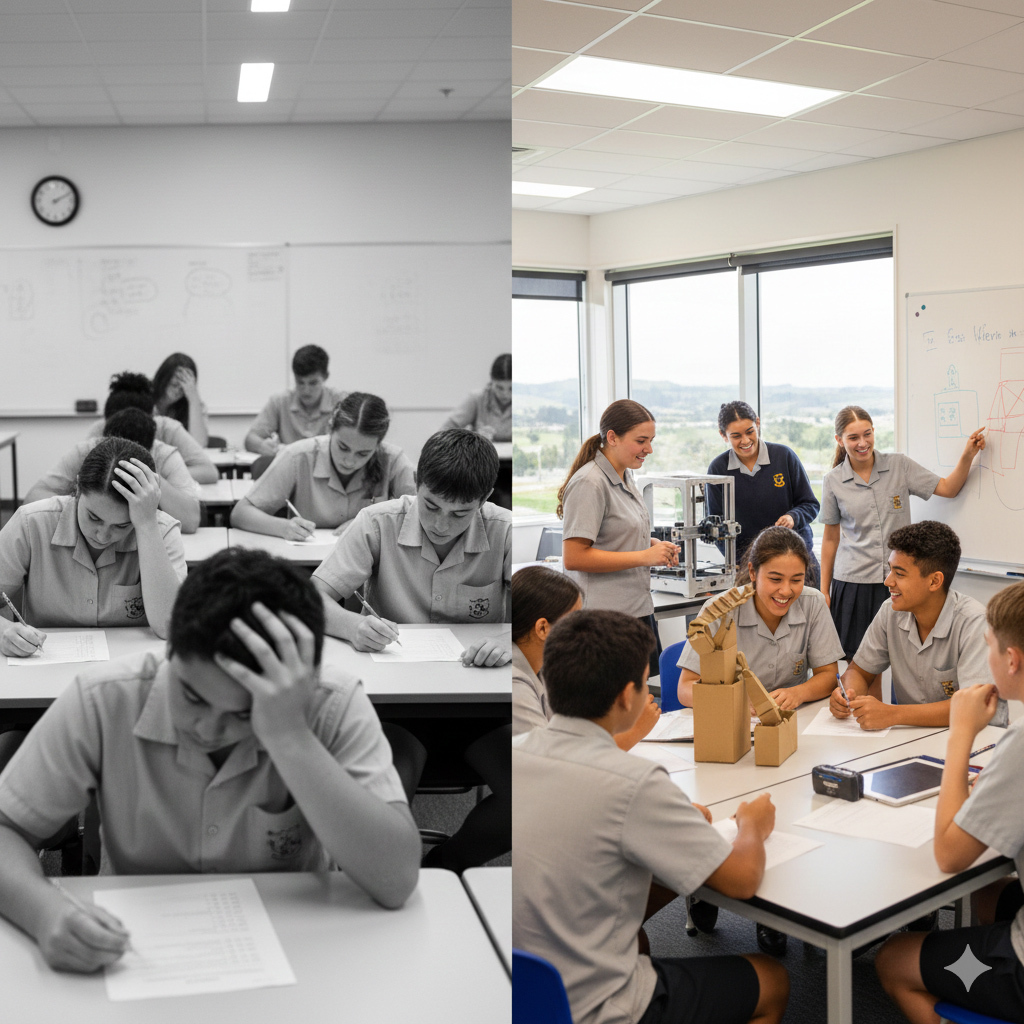

The unprecedented disruption experienced across New Zealand to our lives, our learning and work is well documented. School disengagement is on the rise and traditional education struggles to keep pace with the changes. Businesses struggle to find the talent they need, low skill utilisation and productivity contribute to a sluggish economy and labour market inequities have become increasingly apparent.

It is our belief that micro-credentials and other forms of non-formal learning could be potential solutions to the rapid upskilling that is required. The formal qualification system is becoming challenged, burdened with students’ growing disillusionment of its relevance and its ever-increasing cost. Young people who are disengaging with school, second chance learners and mature learners who have lost jobs or seek to upskill could significantly benefit from having access to micro-credentials, ideally earn as you learn training courses - short form credentials, some of which might be credit-bearing.

Premature departure from school does not signal lack of capability and competence. Often these young people have built a wealth of knowledge and skills in other components of their lives. Capturing the value of these will make a significant contribution to the wellbeing and prosperity of that young person, his or her whānau, community and the wider economy.

The four benefits of non-formal learning are:

• Economic: skill gaps and skill utilisation are improved. Skill recognition assessment models give credit to knowledge and skills gained informally through education, other jobs or in social/cultural contexts. This approach enables training to be precisely targeted, with reduced cost and time for completion and the employee can work while completing the designated courses. Earn as you learn opportunities are essential models for under-served communities.

• Educational: by shortening the time and costs to complete qualifications, without compromising the quality of the learning outcomes.

• Psychological: as young people recognise the skills and attributes they have they become more encouraged, inspired and aspirational of their careers and life goals.

• Equity: educational and labour market equity is improved.

While micro-credentials alone will not meet New Zealand’s future educational needs, it would be a lost opportunity if we do not enable our formal qualification systems to evolve to include them as a valid approach. And we argue that students should be able to access student loans while they complete micro-credential study, as lack of access to student loans creates an unnecessary equity barrier.

For more information about micro-credentials, this report proposes some immediate steps to make micro-credentials work - or work better:

"Making micro-credentials work for learners, employers and providers" by Beverley Oliver, Deakin University